Viscous heating, also known as viscous dissipation, is a crucial phenomenon in fluid mechanics and thermal engineering, where mechanical energy is converted into heat due to the internal friction of a fluid’s molecular layers moving relative to one another. Understanding viscous heating is crucial in various fields, including lubrication, polymer processing, geophysics, biological systems, and high-speed fluid transport. This article provides an overview of the mechanisms behind viscous heating, its mathematical modeling, and key applications

Description

In any real fluid flow, viscosity causes internal friction between fluid layers moving at different velocities. When a fluid is deformed, such as in shear flow, some of the mechanical energy used to drive the flow is inevitably transformed into heat (Figure 1). This process, known as viscous heating, can substantially influence temperature distributions and energy balances, especially in high-shear or high-viscosity environments. In some practical systems, like lubricated bearings, extruders, and natural magma flows, viscous heating is a key factor that engineers and scientists must consider

Figure 1

Origin and Mechanism of Viscous Heating

When a fluid or soft material is subjected to shear or mechanical force, energy is required to move molecular components. A portion of this energy is consumed in overcoming the internal friction between molecules and is directly converted into heat. Simply put, the higher the shear rate or viscosity, the more heat is generated. In systems where heat cannot quickly dissipate from the sample—such as in cells with large thickness or high thermal insulation—generated heat accumulates, causing a local temperature rise, particularly at the center of the sample or in areas far from the cooled walls of measurement devices

The rate of viscous heat generation per unit volume, denoted as Φ (phi), can be expressed mathematically as

:where

In more complex three-dimensional flows, Φ is expressed using the components of the viscous stress tensor and the strain rate tensor

Energy Equation with Viscous Dissipation

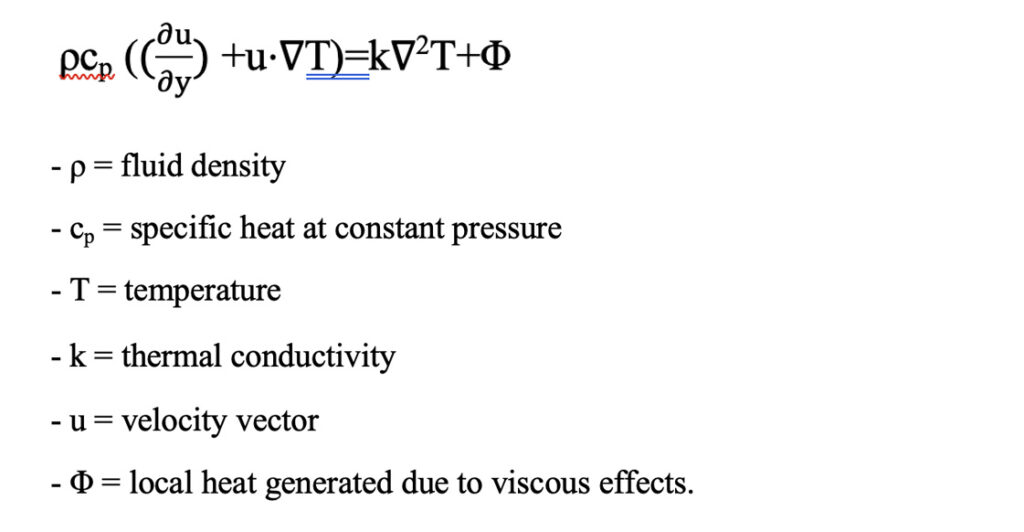

The conservation of energy equation for an incompressible fluid, including viscous dissipation, is represented as

:where

Quantifying the Importance of Viscous Heating: The Brinkman Number

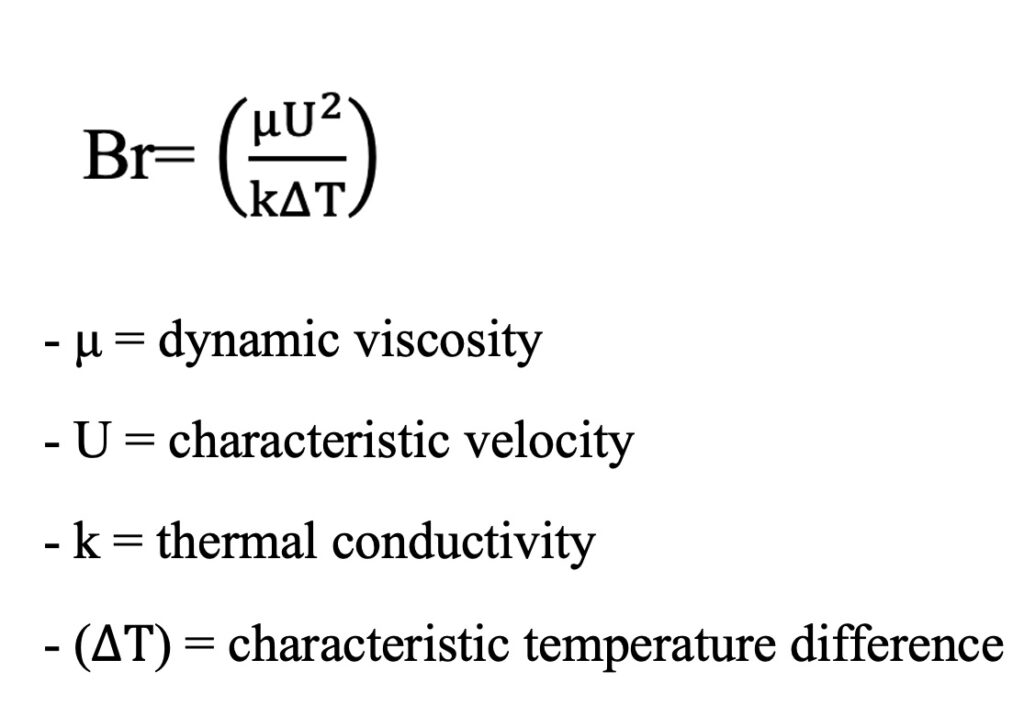

The Brinkman number provides a dimensionless measure of the relative significance of viscous heating to heat conduction

:where

A high Brinkman number indicates that viscous heating is significant compared to thermal conduction. In practical engineering, processes with high fluid viscosities, high velocities, or narrow channels (causing high shear) often produce significant Br numbers

Figure 2 illustrates the exemplary Brinkman number map for representative flow regimes. The heatmap shows the variation of the Brinkman number over a range of dynamic viscosities and characteristic velocities

Figure 2

In this map, the color scale (logarithmic) emphasizes the wide range of possible Br magnitudes from 10-3 (practically no viscous heating) to 104 (strong viscous heating). Some example fluids are overlaid to highlight the applicability of the framework

– Microfluidics (very low , low velocity) lies in the low Br regime

– Lubricated bearings occupy the mid-Br range, where viscous heating can influence lubricant performance

– Polymer extrusion and magma flow fall in higher Br regions where temperature rise strongly impacts rheology

– Turbine blade boundary layers demonstrate extremely high Br due to high velocities despite low viscosity, relevant for thermal protection system design

Want to know more about oils? Check out our article on Industrial Oils: Characteristics, Classification & Application for detailed insights.

Impact of Viscous Heating on Rheological Properties of the Sample

Temperature elevation strongly affects the behavior of fluids, especially their viscosity. Typically, as materials heat up, their viscosity decreases. Therefore, if the sample is heated during rheometry, the measured viscosity values will be lower than the true values at the initial temperature, and the data will reflect the properties of the heated material rather than those of the original sample. This can lead to misinterpretation of non-Newtonian behavior or flow characteristics. Additionally, increased heat may disrupt temperature-sensitive structures or gel networks, causing even more dramatic changes in mechanical properties

Figure 3 illustrates the temperature rise due to viscous heating at different viscosities. This plot shows the estimated steady-state temperature rise () as a function of shear rate (γ̇) for fluids of low (1 mPa·s), medium (100 mPa·s), and high (1 Pa·s) dynamic viscosity. The temperature rise is calculated from the balance between viscous heating (Φ = μ γ̇ 2) and conductive heat removal under representative thermal conductivities

Figure 3

The graph demonstrates that for low-viscosity fluids, significant temperature increases occur only at very

high shear rates, while for high-viscosity fluids, even moderate shear can yield appreciable heating. Some example fluids are overlaid to contextualize the curves

– Microfluidic flows (low viscosity, low shear) produce negligible heating

– Lubrication films in bearings operate in the mid-range, where viscous heating can reduce lubricant viscosity and affect performance

– Polymer extrusion (high viscosity, high shear) produces substantial temperature rises, influencing melt behavior and requiring thermal control in processing

Thermal Gradient and Temperature Nonuniformity in the Sample

A major issue during viscous heating is the creation of temperature gradients within the sample. Typically, the temperature at the sample’s center or furthest from the cooling surface is higher. This issue worsens with very high viscosity materials and high shear rates. In these cases, simply measuring the tool or cell surface temperature is insufficient; true temperature monitoring is required within various sample locations

Thermal gradients also cause local changes in properties such as viscosity and yield stress, and may even create secondary flows within the sample, leading to disturbances in rheological behavior and increased complexity in data interpretation

Effect of Viscous Heating in Industrial and Laboratory Measurements

In many industries, the rheological properties of materials not only depend on production processes but also play a decisive role in final product quality. For example, in plastics, masterbatch, paint, food, and lubricants industries, high temperatures resulting from shear can cause viscosity loss or even destruction of the base material during either testing or processing. Therefore, if viscous heating is not properly managed, the obtained results cannot be generalized to real operational or processing conditions

Experimental Remedies for Reducing or Controlling Viscous Heating Error

Several practical solutions have been suggested to minimize this effect. the most notable of which are

– Lowering shear rates or using shorter tests

– Selecting rheometer tools with smaller gaps or sample cells with greater thermal contact surfaces

– Continuously calibrating temperature sensors and recording real-time temperatures

– Simultaneously recording temperature and viscosity and correcting the data using temperature functions

– Employing theoretical heating models to correct experimental data

In some instances, if complete elimination of error is impossible, data are instead converted to normal conditions using temperature correction models, or graphs are reported based on actual measured temperatures

Applications and Effects

Lubrication Systems

Viscous heating is critical in lubrication engineering, especially for high-speed and high-load contacts such as journal bearings, rolling element bearings, and gearboxes. The heat generated due to viscous shear can raise lubricant temperature, reducing viscosity and potentially compromising lubrication and increasing wear risk. In such cases, accurate thermal analysis is needed to avoid thermal failures

Polymer Processing

During polymer extrusion and injection molding, the highly viscous nature of polymer melts combined with high shear rates leads to significant viscous heating. Uncontrolled temperature rise can result in polymer degradation, color changes, or defects in the final product. Computational models that include viscous dissipation are essential for predicting and controlling temperature profiles in these processes

Geophysical Flows

In earth sciences, viscous heating is considered in magma flows, glacier movements, and the mantle’s convection. For example, viscous heating can contribute to the melting of ice in glaciers or alter the temperature distribution in Earth’s mantle, affecting tectonic activity

Microfluidics & Biological Systems

At the microscale, viscous heating can be significant due to the high surface area-to-volume ratio and large velocity gradients. In microfluidic devices used for biological assays or chemical synthesis, even modest flow rates can produce considerable temperature rises, affecting sensitive biological samples or chemical reactions

High-Speed Flows

In aerospace and high-speed gas flow applications, such as in turbine blades or supersonic flights, viscous heating in the boundary layer can significantly raise the surface temperature of components, influencing materials choice and cooling strategies

Challenges and Future Directions

While viscous heating is well-understood in classical Newtonian fluids, challenges remain, especially for

– Complex, non-Newtonian, shear-thinning or shear-thickening fluids

– Micro and nanoscale flows where unique physical effects arise

– Coupling viscous heating with chemical reactions, as in self-heating slurries or energetic materials

Emerging technologies—such as advanced lubrication, additive manufacturing, and microfluidics—continue to drive research in accurately predicting and managing viscous heating

Conclusion

Viscous heating is a fundamental thermomechanical effect in fluid dynamics, impacting many scientific and industrial applications. Understanding its mechanisms, quantification, and control is critical for designing safe, efficient, and durable systems in lubrication engineering, polymer processing, geophysics, microfluidics, and beyond. Continued research and modeling efforts are expanding our ability to manage viscous heating in ever more complex and miniaturized technologies

Interested in improving lubrication systems? Read our guide on Lubricant Efficiency Optimization: Best Practices to Reduce Waste to boost performance and cut costs.

Viscous Heating: Frequently Asked Questions

Viscous heating occurs when fluid molecules rub against each other during flow, turning mechanical energy into heat.

No. It can occur in both low- and high-viscosity fluids, but its effects are stronger in thick or high-shear flows.

It’s often assessed using parameters like the Brinkman number or by monitoring temperature changes during flow.

Yes. Excessive heat from viscous dissipation can degrade lubricants, polymers, and temperature-sensitive materials.

It appears in applications like lubrication systems, polymer extrusion, turbine operation, and microfluidic devices.

By lowering shear rates, improving cooling, reducing fluid viscosity, or optimizing equipment design.

Yes. It can cause viscosity readings to drop due to temperature rise, giving misleading results.

Absolutely. It plays a role in magma flow, glacier melting, and other geophysical processes.

Yes. Computational models and mathematical equations help forecast heating effects early in the design phase.

Not always. In some processes, it can be beneficial, such as aiding polymer flow or reducing pumping power.

Home

Home Products

Products About Us

About Us Contact Us

Contact Us

no comment