The physical properties of lubricants are measured by characteristics such as viscosity, shear stability, high- and low-temperature performance, water resistance, and volatility. Lubrication specialists work to enhance lubricant performance by controlling these properties through the selection of various base oils and additives. A lubricant’s viscosity and how it changes under different temperatures and operating conditions are one of the most important properties that determine lubricant performance and protection. Accordingly, viscosity is often among the first parameters tested in oil analysis laboratories. But what are we actually referring to when we mention the viscosity of oil?

What is Oil Viscosity?

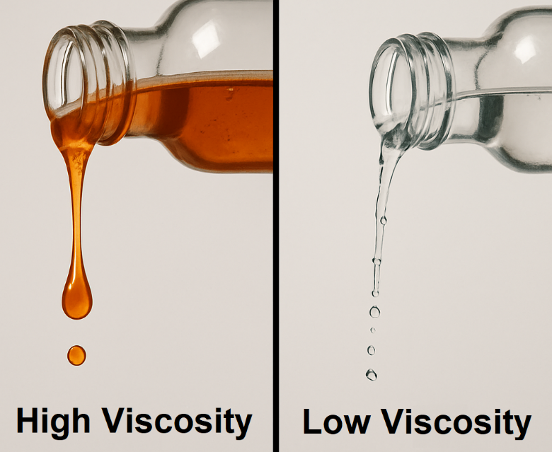

Oil viscosity in refers to its resistance to flow by internal friction. When a fluid is subjected to an external force, such as gravity, its molecules move against each other, creating molecular-level friction that resists the fluid’s flow. A fluid with greater internal friction will have a higher viscosity. Viscosity can be described as the quotient of shear stress (applied pressure) divided by shear rate (rate of flow). This characteristic, which dictates how a fluid responds to variations in temperature and pressure, is crucial in assessing its ability to carry out the essential roles of a lubricant.

Factors That Affect Oil Viscosity

Various factors can affect the viscosity of a liquid, including:

Temperature

As the temperature drops, a lubricant’s viscosity increases, making it thicker and more resistant to flow. When the temperature falls below a specific limit—known as the pour point—the oil can solidify completely. While increased thickness can enhance the lubricant’s ability to bear heavier loads, it also restricts its circulation within the system. Conversely, at higher temperatures, the oil becomes thinner as its molecules gain energy, reducing internal friction and lowering viscosity. This thinning effect can compromise the lubricant’s capacity to prevent metal-to-metal contact. Because viscosity changes with temperature, most equipment manufacturers provide temperature–viscosity charts that indicate the recommended range for optimal performance. Lubrication engineers then select the most suitable viscosity according to the equipment’s design, operating environment, and application needs. Although temperature plays a key role in determining viscosity, other factors can also influence this critical property.

Pressure

The influence of pressure on lubricant viscosity is complex and often underestimated. In certain applications, such as elastohydrodynamic lubrication, pressure–viscosity behavior is a key factor in film thickness calculations, as pressure can cause a sharp rise in oil viscosity. For example, in metal-forming operations, extreme pressures can raise viscosity by up to tenfold, providing critical surface protection. However, the opposite can also occur under mechanical shear—where excessive pressure lowers viscosity, weakening film strength and increasing the risk of metal-to-metal contact and wear.

While compensating with a higher-viscosity oil may seem logical, doing so can restrict flow through narrow channels, leading to oil starvation. The relationship between shear stress and shear rate under pressure also depends on fluid type: In Newtonian oils, the shear rate is directly proportional to the applied shear stress at a constant temperature, allowing viscosity to be clearly defined once the temperature is fixed. By contrast, non-Newtonian fluids such as greases require a shear stress beyond their yield point before they begin to flow. The viscosity measured for such materials is referred to as apparent viscosity and must always be stated alongside the specific temperature and flow rate under which it was determined. Selecting the correct viscosity for the intended operating pressure and conditions is therefore essential to ensure proper circulation and film strength without sacrificing lubrication efficiency.

Shear Rate

In Newtonian fluids, viscosity remains constant regardless of the shear rate. By definition, for Newtonian fluids, such as standard lubricating oils, viscosity acts as a fixed proportional factor between shear force and shear rate. As a result, even under higher shear forces, their viscosity does not change.

In contrast, non‑Newtonian fluids display a viscosity that varies with shear rate. Examples include pseudoplastic fluids, dilatant fluids, and Bingham plastics. A Bingham plastic, such as grease, behaves like a solid until a specific yield stress is exceeded, after which it begins to flow.

The shear experienced by a lubricant can also influence its viscosity over time. For example, viscosity index improvers made from long‑chain polymers may break down under shear, reducing the oil’s viscosity. Likewise, in some non‑Newtonian materials such as grease, viscosity decreases as shear rate increases.

Oil Type, Composition, and Additives

A finished lubricant typically contains a combination of base oil and performance‑enhancing additives. The properties of the base oil play a major role in setting the lubricant’s overall viscosity. However, the use of viscosity index improvers allows manufacturers to tailor the final viscosity to specific needs, independent of the base oil’s original characteristics.

Interested in sustainable lubrication solutions?

Discover how eco-friendly industrial oils are shaping the future of performance and environmental safety.

Read more: Eco‑Friendly Industrial Oils: Role, Benefits, and Future

Measuring Oil Viscosity

Viscosity is among the most critical properties of any oil, playing a decisive role in its ability to protect and lubricate mechanical components. In used‑oil analysis, viscosity testing stands out for its high level of repeatability and reliability. Likewise, no single property of the base oil is more important for maintaining effective lubrication. For this reason, understanding how viscosity is measured and expressed is essential.

Viscosity is generally classified into two main forms: dynamic (also referred to as absolute) and kinematic viscosity. Although the definitions of these two measurements may appear comparable, each reflects different aspects of a fluid’s resistance to flow and serves specific purposes in lubrication assessment.

The dynamic viscosity describes the amount of force required to move one fluid layer past another, effectively representing the liquid’s internal resistance to flow. It is typically reported in centipoise (cP) or in SI units as pascal‑seconds (Pa·s), where 1 Pa·s equals 10 poise. This property is a key factor when performing calculations for elastohydrodynamic lubrication, such as those involving rolling bearings and gear teeth contacts.

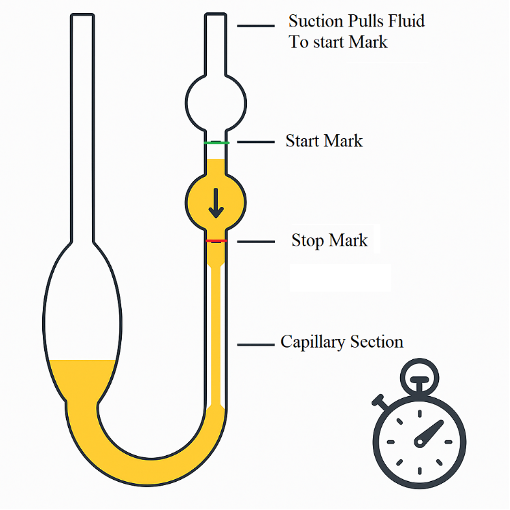

The kinematic viscosity, on the other hand, represents a fluid’s resistance to flow when acted upon solely by gravity. It is determined by recording the time, in seconds, that a set volume of liquid takes to travel a fixed distance through a capillary tube in a calibrated viscometer, under a precisely maintained temperature. The standard unit is the centistoke (cSt), equivalent in SI terms to 1 mm²/s (1 cSt = 1 mm²/s). For accuracy and comparability, viscosity values must always be reported together with the test temperature, for example, a reading of 23 cSt at 40 °C.

Distinction Between Kinematic and Absolute Viscosity

Accordingly, the key difference between these two is that kinematic viscosity is determined by observing how a liquid flow under the pull of gravity alone, whereas absolute (dynamic) viscosity is measured by assessing the resistance a fluid presents when subjected to an applied force, such as moving a solid object through it or pushing it through a capillary under controlled conditions. The two are linked mathematically, with kinematic viscosity obtained by dividing the dynamic viscosity by the fluid’s density (or specific gravity):

Kinematic Viscosity = Dynamic Viscosity/ Density

Other units for viscosity measurement include Saybolt, Redwood, or Engler. However, these units are less widely used compared to the more standard centistoke (cSt) and centipoise (cP) units used for lubricant testing.

Viscosity Measurement Methods

A variety of techniques are available for measuring viscosity, each offering its own benefits depending on the application. The following are the most widely used approaches for assessing base oil viscosity.

Capillary Viscometer

A capillary viscometer consists of a glass tube in the general U-shape, which is commonly known as a U-tube. In this procedure, the U-tube is submerged in a temperature-controlled bath (usually at 40 or 100 °C) and the time is precisely recorded (in seconds) for the time it takes for a fixed amount of fluid to flow within the tube from one marked point to another under the force of gravity or suction. The measured time is then multiplied by a constant (related to the particular tube) to quantify the kinematic viscosity (gravity force) or the absolute viscosity (suction). A schematic of the capillary viscometer is shown in Figure 1.

figure 1

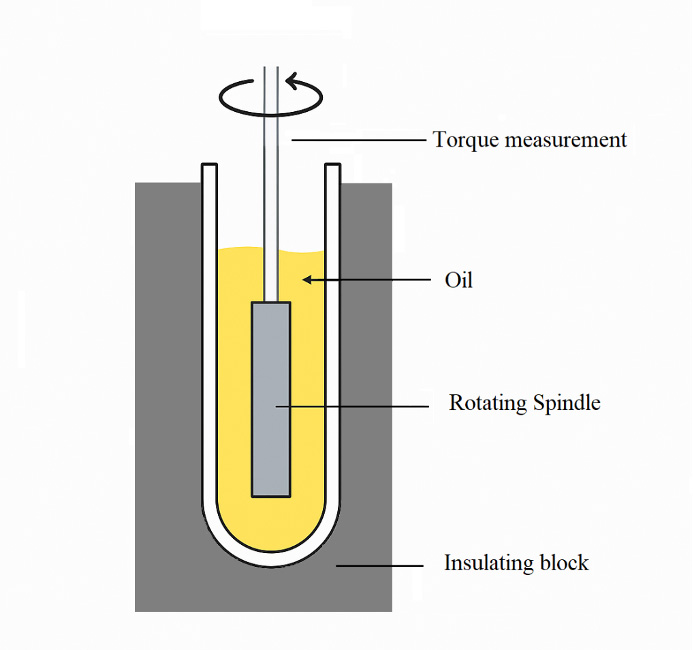

Rotational Viscometer

A rotational viscometer measures viscosity by placing a rotating element, known as a spindle, into the fluid being tested (Figure 2). The torque required to turn the spindle provides a measure of the liquid’s resistance to movement. Unlike methods based on gravity, this technique relies on the relationship between the fluid’s internal shear stress and the applied motion, allowing it to determine the fluid’s absolute (dynamic) viscosity. One well-known example of this instrument is the Brookfield viscometer. A more advanced design is the Stabinger viscometer, which uses a free-floating spindle driven by electromagnetic forces. This setup offers a key advantage: it removes the complications of compensating for bearing friction from a motor directly connected to the spindle.

figure 2

While rotational and capillary viscometers are the most common choices, other techniques can also be used, particularly for specialized applications.

Falling Ball and Falling Piston Tests

In these methods, a sphere or piston is released into the test fluid, and the time it takes to travel between two fixed reference points is recorded. To determine viscosity using Stokes’ law, the terminal velocity, size, and density of the falling object must be known. These calculations directly relate the object’s motion through the fluid to its resistance to flow.

Additional Techniques

Less frequently in oil testing, the bubble method may be applied. Here, the time required for a bubble to rise through a set distance is measured, and this time is then correlated to the fluid’s viscosity. Another specialized approach uses a vibrating probe, where viscosity is determined by measuring the damping effect the fluid has on the probe’s oscillations.

Summary

Oil viscosity, defined as a fluid’s resistance to flow due to internal friction, is one of the most critical properties influencing a lubricant’s ability to protect and perform under varying operating conditions. It is affected by various parameters, including temperature, pressure, shear rate, and oil composition. Viscosity is commonly classified as dynamic (absolute) or kinematic viscosity, each measured using specific units and methods, including capillary, rotational viscometers. Selecting the correct viscosity ensures optimal film thickness, circulation, and load-carrying capacity, while improper selection can lead to wear, oil starvation, or reduced efficiency. Accurate measurement and reporting, including test temperature, are essential for proper lubricant analysis and application.

Want to build a solid understanding of lubrication?

Explore the core principles that keep machinery running smoothly.

Oil Viscosity Explained: Your FAQ Guide

It shows how easily or slowly an oil flows, which is directly related to the internal friction between its molecules.

Cold conditions make oil thicker and slower to flow, while heat thins it and can reduce protection.

It determines how well oil can form a protective film and circulate efficiently in moving parts.

Dynamic viscosity measures resistance to motion under force, while kinematic viscosity measures flow under gravity.

Yes. High pressure can increase viscosity, but excessive mechanical shear can also reduce it.

Common tools include capillary viscometers, rotational viscometers, and falling ball/piston methods.

Yes. Additives like viscosity index improvers help oils maintain stable performance at varying temperatures.

Always include the temperature at which it was measured, e.g., “46 cSt at 40 °C.”

Home

Home Products

Products About Us

About Us Contact Us

Contact Us

no comment