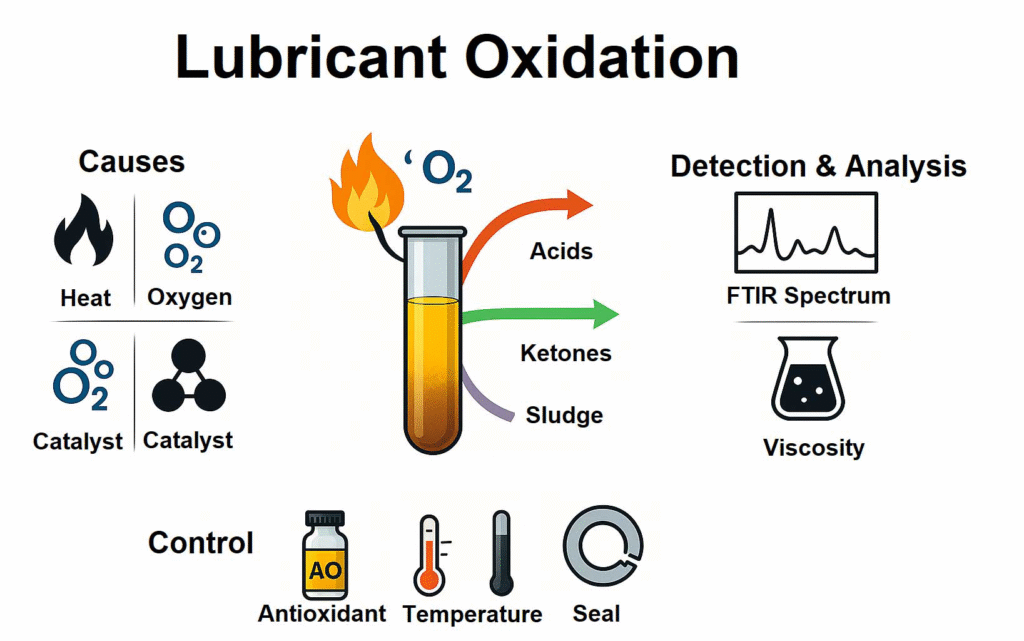

During operation, lubricants are exposed to air, heat, pressure, corrosive substances, and many other factors that trigger chemical changes in the oil. These changes may impair the lubricant’s effectiveness, especially if essential additives are consumed or degraded. Over time, such chemical reactions can lead to the accumulation of undesirable degradation products, like weak organic acids. Routine oil analysis typically assesses lubricant oxidation levels. Oxidation is the primary chemical process affecting lubricants during use which can lead to a wide range of lubricant issues, like a rise in viscosity, the development of varnish, sludge, and sediment, depletion of additives, base oil breakdown, filter plugging, corrosion, loss in foam control, an increase in acid number (AN), and rust formation. Therefore, understanding, monitoring, and controlling oxidation is crucial for lubricant management

The Process of Lubricant Oxidation

Lubricant oxidation reaction begins with the formation of a highly reactive free radical, which then initiates a chain reaction. These free radicals continue to react, generating additional radicals that aggressively attack the base oil, accelerating the degradation process

Almost all lubricants are formulated with antioxidants. These substances are designed to be sacrificial, reacting with the free radicals to neutralize them and protect the base oil. However, once the antioxidants are depleted, free radicals start to attack the base oil. At this stage, polymerization may occur, leading to the formation of deposits within the lubricant

The rate of oxidation changes significantly with temperature and is further influenced by contaminants (especially metals) found in the lubricant. Therefore, maintaining the oil dry, clean, and cool state is the most effective strategy for oxidation management

Three Steps of Lubricant Oxidation and How to Control It

The oxidation process of a hydrocarbon fluid occurs in three basic phases: initiation, propagation, and termination. Controlling oxidation is possible by targeting one or more of these key stages. This is achieved by restricting the availability of oxygen during initiation, reducing the number of propagation cycles, or employing additional termination strategies to stop the reaction. Lubricant formulations often integrate a combination of these approaches. Since initiation marks the beginning of oxidation, limiting oxygen exposure serves as the primary defense

By identifying the factors that drive the propagation stage, it becomes possible to further minimize oxidation. The process ends at the termination stage. Here, antioxidants play an essential role by interrupting propagation and forming stable radicals, thereby ending the reaction cycle. Monitoring the condition of these antioxidants is one of the most effective methods for assessing the overall health of a lubricant

Discover how eco-friendly industrial lubricants can reduce pollution and support long-term sustainability. Read the full article now and take your first step toward greener operations.

Impact of Oxidation on Lubricant Characteristics

Oxidation is the main chemical process that leads to lubricant in-service deterioration. Lubricant oxidation of an oil occurs when long molecular chains break down into shorter ones, triggering changes in the lubricant’s chemical composition. This process becomes intricate when oxidation impacts a larger proportion of molecules in the lubricant, and distinct changes in performance become evident

By altering the chemical structure of molecules, their ability to bear loads between moving surfaces changes. This structural change also affects how these molecules interact with the remaining, unaltered lubricant molecules, resulting in increased viscous heating [Viscous heating, also known as viscous dissipation, is the irreversible process where mechanical energy is converted into heat due to friction between layers of a fluid in motion.]

The rise in viscosity is often linked to the formation of larger molecules or substances, such as sludge, through processes like polymerization. Even just the splitting of hydrocarbon chains by oxidation introduces variability among molecules, making the overall mixture less uniform and leading to resistance within the fluid

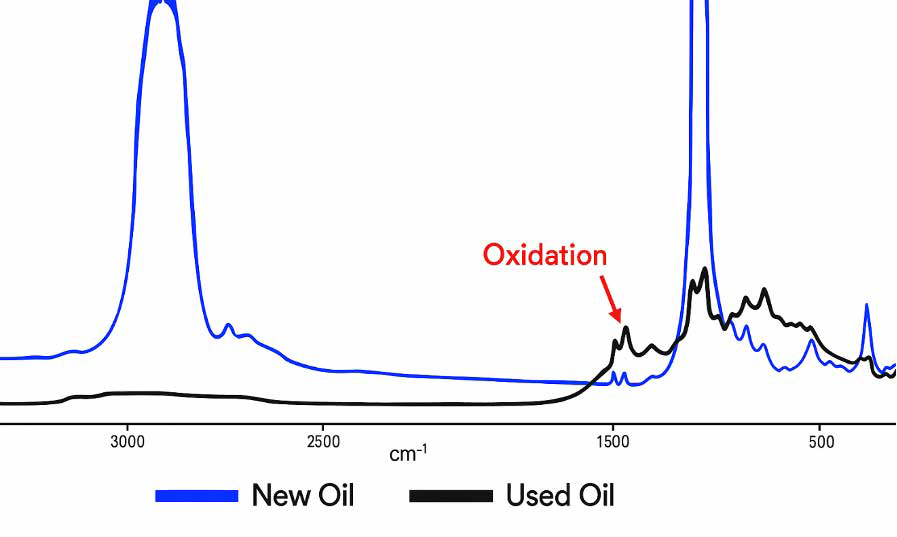

Before oxidation, oil molecules are similar in size and shape, providing easy flow. However, the new compounds generated by oxidation give rise to new intermolecular forces. For example, carboxylic acids formed during this process tend to associate with each other, behaving as larger units known as dimers. This phenomenon can be identified on the infrared spectrum by a carbonyl absorption peak near 1710 cm-1, which reveals the presence of these associated carbonyls, in contrast to the peak at 1760 cm-1 found in unassociated states. The cumulative result is higher molecular resistance to movement, resulting in increased viscosity throughout the lubricant

Methods for detecting lubricant oxidation

Despite the presence of antioxidants in almost all lubricant formulations, breakdown and oxidation of the lubricant are inevitable. Oil undergoing oxidation emits several warning signs, many of which can be identified through oil analysis. So, various tests have been developed to evaluate the state of the lubricant oxidation. The following section introduces the most common methods for detecting lubricant oxidation

Total Acid Number (TAN)

As mentioned earlier, the oxidation process results in the formation of organic acids. These acids can be identified through a rise in the Total Acid Number (TAN), which reflects the acid content of the oil. The TAN is determined by measuring the volume of a basic solution, typically potassium hydroxide, required to neutralize the acids present in the sample. However, the TAN test does not distinguish between acids produced by oxidation and those introduced from external contamination. Additionally, certain additives, including anti-wear agents, extreme pressure additives, and some rust inhibitors, are inherently acidic. These contribute to a higher initial TAN, which may decrease as the additives are consumed over time

Viscosity

Viscosity represents a fluid’s resistance to flow. The association or condensation of oxidation byproducts, like carboxylic acids, will increase the viscosity. Monitoring changes in viscosity is vital, regardless of the underlying cause, which is why viscosity testing is a standard component of lubricant condition monitoring. Various testing methods are employed, such as ASTM D445 and ASTM 7279, with specialized instruments available for both laboratory and on-site use. For example, the Spectro Scientific MiniVisc 3000 portable kinematic viscometer is commonly utilized in field testing

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

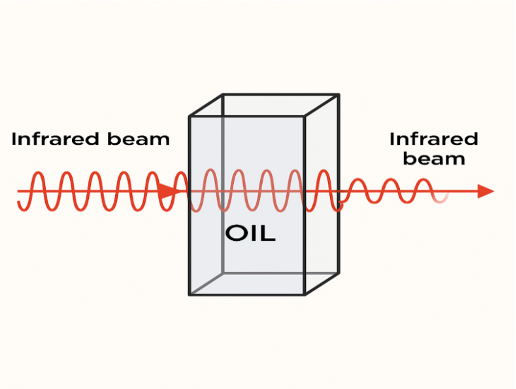

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) is a powerful tool for evaluating the properties of used fluids and monitoring their condition. This technique works by passing an infrared beam through the oil sample (Figure 1). Each molecule absorbs infrared energy at a specific frequency. As oil oxidizes, its hydrocarbons are converted into carboxylic acids, ketones, aldehydes, and alcohols. These new compounds can be detected and identified by an FTIR spectrometer

In the example shown in Figure 2, the elevated oxidation levels are indicated by the FTIR analysis compared to the values of the new lubricant

Darker Appearance

As oxidation occurs, oil typically becomes darker in color. Although a darker shade does not always confirm that the oil is oxidized or deteriorated, it can serve as a warning sign

Unpleasant Smell

Oxidized oil frequently develops an offensive odor. Oils containing sulfur compounds, either from the base oil itself or from sulfur-based additives, may emit a smell similar to rotten eggs

Summary

Lubricant oxidation is a serious issue that not only diminishes the lubricant’s performance but also leads to the formation of acids that can accelerate component corrosion and wear. Therefore, understanding how and why oxidation occurs, as well as recognizing the warning signals via oil analysis, is essential. Also, monitoring and managing oxidation is crucial to achieving optimal lubrication performance

FAQ Lubricant Oxidation

Antioxidants delay oxidation by reacting with free radicals before they can attack the base oil. They act as sacrificial agents, meaning they are consumed during the protection process. Once depleted, the oil becomes much more vulnerable to rapid degradation.

Yes. Although higher temperatures accelerate oxidation, the process can still happen slowly under moderate conditions, especially if other catalytic factors like moisture, metal particles, or poor ventilation are present.

Oxidation generates acids and polymers that increase molecular interactions. Over time, this leads to thicker oil, which increases drag and reduces the lubricant’s ability to flow and provide proper lubrication.

In most cases, yes. Byproducts such as sludge, varnish, and carboxylic acids can clog filters, corrode surfaces, and impair heat transfer, even if they initially appear in small amounts.

FTIR spectroscopy is highly effective for detecting the early formation of oxidation-related chemical groups, such as carbonyls, before visible symptoms like color change or sludge appear.

Switching lubricants can help prevent further damage by introducing fresh oil with active antioxidants. However, it won’t reverse existing deposits or corrosion, so corrective maintenance may still be required.

As oxidation progresses, organic acids form, which increases the acid number. Regular acid number monitoring helps track the rate of oxidation and determine the appropriate time for oil changes.

Lubricants stored in hot, humid, or poorly sealed containers absorb oxygen and moisture more quickly. Storing oil in a cool, dry, and sealed environment greatly reduces the chance of oxidation before use.

Home

Home Products

Products About Us

About Us Contact Us

Contact Us

no comment