The performance and reliability of lubricants in industrial machinery depend strongly on their chemical composition. Additive elements such as barium, boron, calcium, copper, magnesium, molybdenum, phosphorus, sulfur, and zinc are added to lubricating oils to enhance key properties, including wear protection, corrosion resistance, oxidation stability, and friction reduction. The concentration of additives significantly affects the performance of lubricants under operational conditions. Therefore, accurate measurement of these additives is essential for effective production and quality control. This article summarizes the principal techniques used for elemental analysis of industrial lubricants and related ASTM standard methods, and discusses the major associated analytical challenges.

Background

Elemental analysis is the backbone of an effective oil analysis program. Its history dates back to the 1940s and 1950s, when it was utilized in the railroad industry to detect the presence of wear metals in diesel engine oils. Initial tests demonstrated that tracking elements related to wear and contamination offered early alerts for chronic equipment failures.

Generally, elemental analysis of industrial lubricants serves four key purposes:

Performance Optimization: Identifying wear metals and contaminants helps protect equipment from damage, improves efficiency, and lowers maintenance costs.

Failure Analysis: Detecting abnormal elemental signatures helps diagnose mechanical problems and prevent repeat failures.

Quality Control (QC): Precise Elemental analysis ensures lubricant formulations meet required performance specifications.

Regulatory compliance: Demonstrates analytical accuracy using standardized methods such as ASTM Petroleum Standards.

Analytical Techniques for Elemental Analysis of Industrial Lubricants

Elemental analysis of industrial lubricants is most often performed based on atomic emission spectroscopy (AES) using advanced spectrometric techniques, including Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP‑OES/ICP‑AES) and Rotating Disk Electrode Optical Emission Spectrometry (RDE‑OES/RDE‑AES). In AES, individual atoms within a sample, such as zinc atoms from a ZDDP additive molecule, iron atoms from wear debris, or silicon from silica (dirt) contamination, are excited using a high-energy source. Table 1 provides an overview of common elements measured and their typical sources.

Table 1-an overview of common elements measured in elemental analysis of industrial lubricants and their typical sources.

| Element | Origin | Most common source |

| Iron (Fe) | Wear metal | Various iron and steel machine parts |

| Lead (Pb) | Wear metal | Journal bearings, babbitt, bronze alloys |

| Tin (SN) | Wear metal | Bronze alloys, journal bearing flashing |

| Chromium (Cr) | Wear metal | Ring plating, chrome plating, stainless steel |

| Nickel (Ni) | Wear metal | Stainless steel alloy, plating |

| Titanium (Ti) | Wear metal | Gas turbine bearings, turbine blades |

| Silver (Ag) | Wear metal | EMD wrist pin bushings, solder, needle bearings |

| Antimony (Sb) | Wear metal | Journal bearings |

| Vanadium (V) | Wear metal | Turbine blades, valves, bunker fuel |

| Aluminum (Al) | Wear metal | Bearings, dirt, various minerals |

| Zinc (Zn) | Wear metal, additive | Brass alloys, AW additives, galvanizing |

| Copper (Cu) | Wear metal, additive | Cooler core, brass/bronze alloys, babbitt, bushings, slinger rings, anti-seize additive |

| Silicone (Si) | Contaminant, additive | Dirt, antifoam additive, silicone sealants, coolant additive |

| Sodium (Na) | Contaminant | Coolant additive, seawater, process chemicals (caustic) |

| Potassium (P) | Contaminant | Coolant additive, fly ash |

| Lithium (Li) | Additive | Grease thickener |

| Phosphorus (P) | Additive | AW/EP additive |

| Molybdenum (MO) | Additive | EP additive |

| Barium (Ba) | Additive | Detergent additive |

| Calcium (Ca) | Additive, contaminant | Detergent additive, cement dust, various minerals, hard water |

| Magnesium (Mg) | Additive, contaminant | Detergent additive, Seawater |

| Boron (B) | Additive, contaminant | EP additive, detergent, coolant inhibitor |

The fundamental distinction between ICP and RDE lies in how the sample is vaporized and how its constituent atoms are excited by the high‑energy source.

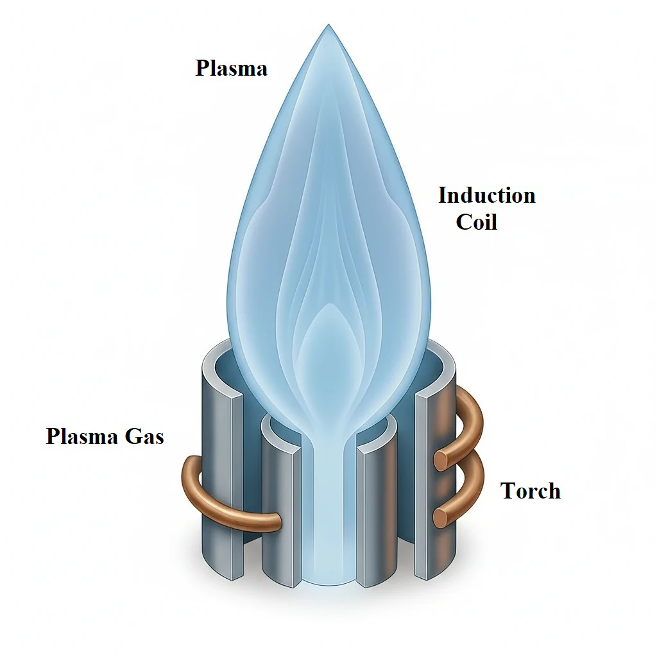

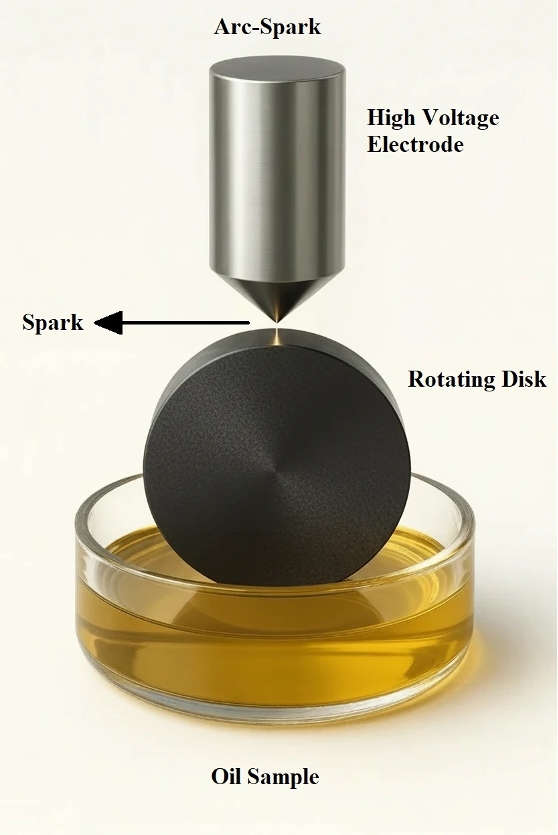

In an ICP spectrometer, the oil sample is introduced into a high‑temperature argon plasma, where it undergoes vaporization, atomization, and excitation, leading the atoms to emit characteristic radiation. In contrast, an RDE spectrometer vaporizes and excites the sample using a high‑voltage discharge formed between a stationary electrode and a rotating carbon disc. A schematic of an ICP device and an RDE device is shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

Figure 1

Beyond the excitation source, the remaining components of ICP and RDE instruments function in much the same way. The emitted light is collected and directed onto the entrance slit of the spectrometer, where a diffraction grating separates the light into its component wavelengths according to their diffraction angles. The intensity at each wavelength position, commonly referred to as a channel, is detected by a light‑sensitive photodiode. The resulting electrical signal is then converted to elemental concentrations (in ppm) using a straightforward calibration routine. Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (AAS) and X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) are two other spectrometric techniques used in the elemental analysis of Industrial Lubricants.

Figure 2

Advantages and Limitations of Atomic Spectroscopy

Because it can detect unusual wear patterns, contamination, and additive-related anomalies, AES is a highly valuable tool in any oil analysis program. When applied correctly, it can identify problems ranging from corrosive wear to coolant ingress, seawater contamination, or additive depletion. For these reasons, AES remains a foundational technique in well-designed lubricant‑condition monitoring programs.

On the other hand, it is essential to understand how strongly this technique depends on particle size. Because AES can only measure material that is fully vaporized, it performs well for dissolved metals and very fine particles. Still, it loses sensitivity for debris larger than about 5 microns, becoming effectively blind to particles above 10 microns. Since many forms of active mechanical wear generate particles in this larger range, relying solely on AES may miss meaningful indicators of machine distress. For a complete and accurate picture of equipment condition, AES should be complemented with techniques such as particle counting, ferrous density testing, and patch microscopy, all of which capture the coarse debris that AES cannot detect.

Trend Analysis of Elemental Data

When interpreting elemental analysis of industrial lubricants results, the focus should be on how each element changes over time rather than on absolute values. Tracking trends across consecutive samples is critical because wear rates vary widely between machines depending on factors such as design, operating conditions, lubricant type, equipment age, and workload. Evaluating these rates‑of‑change patterns is one of the most effective ways to detect early signs of wear or contamination.

When analyzing AES data, it’s crucial to understand both the machine’s metallurgy and the chemical composition of common contaminants that may be present. This knowledge allows the analyst to relate the data to the active wear of specific components or to identify the ingress of particular contaminants.

It is equally important to know the expected concentrations of metal‑containing additives in the lubricant. To achieve this, fresh oils should be baselined annually or whenever a formulation change is suspected. Comparing this baseline “elemental fingerprint” to the used‑oil data helps identify issues such as additive loss or accidental mixing with an incorrect product.

However, caution is needed when evaluating additive metals: a drop in additive performance does not always correspond to a decrease in the measured concentration of those elements in AES.

To better understand how oxidation affects lubricant chemistry, additive performance, and oil degradation trends, read our in‑depth article Lubricant Oxidation: Analysis, Control, and Detection.

Challenges in Elemental Analysis of Industrial Lubricants

Metal analysis of lubricants and oils presents several challenges, due to the complex composition of these materials and the trace levels at which metals are often present. Some of the major challenges are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2 – Major Challenges in the Elemental Analysis of Industrial Lubricants

| Challenges | Solutions |

| Risk of contamination | Apply strict laboratory protocols; use ultra-pure reagents, clean equipment, and a sterile workspace. |

| Detecting Low Concentrations | Employ highly sensitive analytical techniques for detecting low concentrations of metals |

| Complex Matrix Effects | Use appropriate sample pre-treatment procedures. |

| Matrix-Specific Calibration Challenges | Use matrix-matched certified reference materials and high-quality diluent matrix solvent. |

| Stability of Metallo-Organic Standards | Select solvents that stabilize metals; minimize exposure to moisture/humidity. |

Testing Standards in Elemental Analysis of Industrial Lubricants

ASTM International serves as the primary global authority for petroleum product testing standards, defining precise methods that ensure accuracy and comparability of results across laboratories. By engaging a network of expert scientists, ASTM keeps its procedures up to date, promotes worldwide adoption, and sustains the credibility of petroleum analysis in both technical and commercial contexts.

The key ASTM Methods for elemental analysis of industrial lubricants:

ASTM D5185 – Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) Atomic Emission Spectrometry

ASTM D5185 establishes a method for measuring up to 22 metallic elements in both used and unused lubricants by direct introduction of the sample into an inductively coupled plasma source. The diluted oil (commonly in kerosene or xylene) is nebulized, and the resulting plasma excites atomic emissions recorded by optical spectrometry. D5185 provides high sensitivity and reproducibility, making it the reference technique for laboratory-grade elemental analysis of additives (Ca, Zn, P, Mo) and wear metals (Fe, Cu, Pb, Al, Cr, Ni). It is the most common standard in oil analysis laboratories worldwide.

ASTM D4951 – Elemental Analysis of Additives in Lubricating Oils by ICP-AES

This standard describes a method for determining the content of additive elements, primarily calcium, zinc, phosphorus, sulfur, magnesium, molybdenum, and barium, in fresh lubricating oils using Inductively Coupled Plasma–Atomic Emission Spectrometry (ICP‑AES). Unlike ASTM D5185, which is optimized for both used and unused oils (including wear and contaminant metals), D4951 focuses specifically on formulated additives in new oil samples without interference from wear debris or contaminants. The oil is diluted in a suitable organic solvent and analyzed to verify additive concentration, ensuring formulation accuracy and compliance with oil specifications. Because of its precision and reproducibility, D4951 is regularly employed in quality control and blending verification in lubricant manufacturing.

ASTM D6595 – Rotating Disc Electrode (RDE) Atomic Emission Spectrometry

ASTM D6595 describes the determination of wear metals, contaminants, and additive elements in used lubricating oils using Rotating Disc Electrode atomic emission spectroscopy. In this technique, a rotating graphite disc and a stationary graphite rod form an electrical arc that excites atoms in a thin film of the oil sample. The emitted light from the excited atoms is analyzed for characteristic wavelengths corresponding to different elements. D6595 is widely used in condition monitoring to track machinery wear, contamination, and additive depletion over time, offering rapid multielement analysis with minimal sample preparation.

ASTM D4628 – Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS)

ASTM D4628 describes the analysis of additive metal elements (typically Ca, Zn, Mg, Ba, P) in additive concentrates and lubricating oils by Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy. The process involves dilution or ashing of the sample, followed by flame or graphite‑furnace AAS measurement of each element. Although slower and single-element in nature, AAS offers high accuracy and serves as a reference method for certifying additive packages and verifying ICP or XRF data.

Fuel dilution can significantly alter lubricant viscosity, accelerate additive degradation, and distort elemental analysis trends.

For a detailed understanding of its mechanisms, detection techniques, and prevention strategies, read Fuel Dilution in Lubricants: Mechanisms, Detection, and Prevention in Modern Engines.

Summary

Elemental analysis of industrial lubricants is a foundational diagnostic tool in lubricant condition monitoring because it quantifies wear metals, additive elements, and contaminants with high sensitivity, providing a direct assessment of both lubricant health and machine integrity. These measurements enable early detection of abnormal wear, ingress of contaminants such as dirt, coolant, or seawater, and depletion of critical additive packages, all of which directly influence lubricant performance and equipment reliability. By supporting optimization of lubricant formulation, guiding preventive and predictive maintenance decisions, and ensuring compliance with industrial specifications, elemental analysis of industrial lubricants plays a central role in reducing unplanned downtime and extending component life. Techniques such as ICP‑OES and RDE‑OES offer standardized, reproducible data that form the basis for effective trend analysis and robust asset‑health evaluation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Elemental analysis provides direct insight into lubricant condition by quantifying wear metals, additive elements, and contaminants. This information allows maintenance teams to detect abnormal wear early, verify additive integrity, and ensure lubricants continue to deliver protection under real operating conditions.

Wear metals originate from machine components and indicate mechanical distress or failure mechanisms, while additive elements are intentionally blended into lubricants to enhance performance. Monitoring both allows differentiation between normal additive chemistry and abnormal equipment wear.

Absolute values vary greatly depending on machine design, lubricant formulation, and operating conditions. Trend analysis reveals changes in wear rates or contamination over time, which is far more effective for identifying emerging problems than relying on single test results.

Not always. While elemental analysis measures additive-related metals, chemical degradation or additive surface passivation can reduce performance without a measurable drop in elemental concentration. For full assessment, elemental data should be interpreted alongside oxidation, acidity, and performance testing.

ICP‑OES offers higher sensitivity and precision for dissolved metals and additives, making it ideal for laboratory-based quality control and detailed diagnostics. RDE‑OES provides faster results with minimal sample preparation and is widely used for routine condition monitoring in industrial environments.

Atomic emission techniques can only detect particles small enough to be vaporized. Larger wear debris generated during advanced mechanical damage may not be detected, which is why elemental analysis should be combined with particle counting, ferrous density testing, or analytical ferrography.

Fresh oil baselining defines the lubricant’s original elemental fingerprint and ensures accurate interpretation of future results. It helps distinguish normal additive chemistry from contamination, mixing errors, or incorrect lubricant use.

ASTM standards ensure consistency, accuracy, and reproducibility across laboratories. They define validated procedures for sample preparation, calibration, and measurement, allowing meaningful comparison of results across suppliers, facilities, and time.

Common contaminants include airborne dirt (silicon), coolant leaks (sodium, potassium, boron), process chemicals, seawater (magnesium, sodium), and residual cleaning agents. Identifying these elements helps pinpoint contamination pathways and prevent recurrence.

By detecting abnormal elemental trends before failures occur, elemental analysis allows maintenance teams to intervene early, schedule repairs strategically, and avoid catastrophic equipment damage. It transforms maintenance from reactive to predictive decision-making.

Yes. For new oils, elemental analysis verifies additive composition and formulation accuracy. For used oils, it monitors wear progression, contamination ingress, and additive changes during service.

Industries with high-value rotating equipment—such as power generation, petrochemicals, mining, steel, marine, and manufacturing—benefit significantly due to the high cost of unplanned downtime and component failure.

Sampling frequency depends on equipment criticality, operating severity, and historical performance data. Critical equipment often requires monthly or even more frequent analysis, while stable systems may be monitored quarterly.

No. While essential, elemental analysis should be part of a broader oil analysis program that includes viscosity, oxidation, acidity, cleanliness, and performance testing to fully assess lubricant suitability.

It verifies additive treat rates, confirms batch-to-batch consistency, and ensures compliance with formulation specifications and international standards—reducing the risk of off-spec products reaching the market.

Reference

Noria Corporation, Elemental Analysis Explained and Illustrated.

https://www.machinerylubrication.com/Read/287/elemental-analysis

Elemental Analysis of Oil. https://www.spectrosci.com/knowledge-center/blogs/oil-analysis/elemental-analysis-of-oil

Elemental analysis of industrial lubricants and oils: an overview.

https://www.lgcstandards.com/GL/en/Resources/Articles/elemental-analysis-lubricants-oils

Home

Home Products

Products About Us

About Us Contact Us

Contact Us

no comment