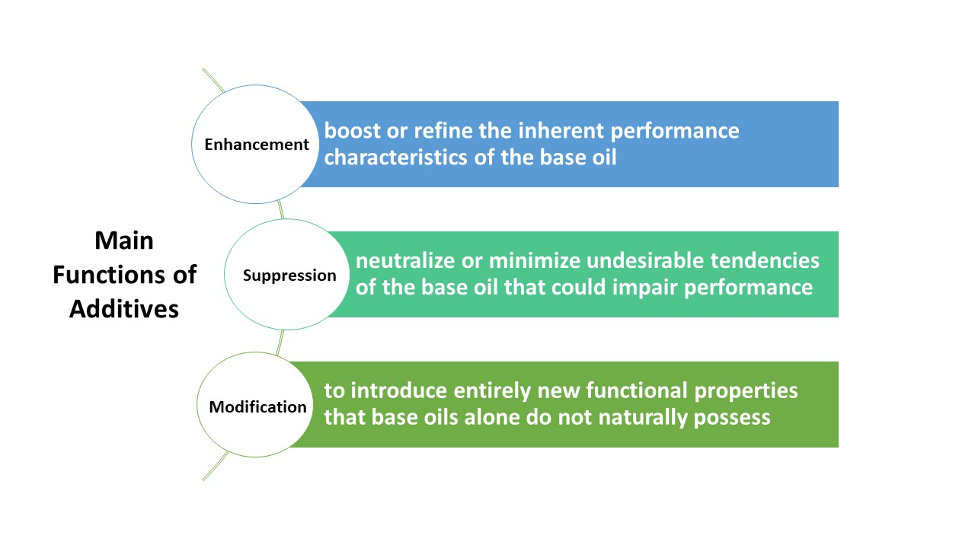

The main ingredient of a lubricant is a base oil. However, base oils often fail to meet all the requirements for effective lubrication during operation. This is why additives are incorporated. Lubricant additives are either organic or inorganic compounds that are dissolved in or suspended as solids in oil. These additives typically make up between 0.1% and 30% of the oil’s volume, depending on the specific machinery in use, and modify the properties of lubricants through both chemical and physical effects. Additives enhance the properties of the base oil, improving its quality, reliability, and overall performance. There are many types of lubricant additives, and the choice of which to use depends on their effectiveness in performing intended functions. Additives are also selected for their compatibility with the chosen base oils, their capacity to mix easily with other additives in the formulation, and their cost-effectiveness. In general, three main functions are considered for lubricant additives: to enhance certain properties, reduce undesirable traits, and potentially introduce new characteristics (Figure 1). Some additives operate within the oil itself, such as antioxidants, while others interact with the surface of metal components, like anti-wear additives and rust inhibitors

To learn more about the different types and applications of industrial base oils, see our detailed article on Industrial Oils; Characteristics, Classification & Application.

Figure 1

Types of Lubricant Additives

Lubricant additives are produced in various types and formulations offered by different suppliers. This section outlines the most common additives present in finished lubricants.

Oxidation Inhibitors (Antioxidants)

Oxidation takes place in nearly all lubricants. While it naturally occurs under normal operating conditions, elevated temperatures and the presence of water or other contaminants, such as wear metals, greatly accelerate the process. During oxidation, free radicals are generated and propagate to form alkyl or peroxy radicals and hydroperoxides, which subsequently react with other molecules to produce various oxidation by‑products.

To counteract oxidation, antioxidants are typically incorporated into lubricants. These kinds of lubricant additives function by neutralizing free radicals or decomposing hydroperoxides during the propagation stage of oxidation. Antioxidants are considered sacrificial additives because they protect the base oil from oxidative degradation at the expense of being consumed themselves. Therefore, they are present in almost all lubricating oils and greases.

Common classes of antioxidants include phenolic compounds, aromatic amines, hindered phenols, aromatic nitrogen derivatives, and zinc dialkyldithiophosphates (ZDDPs), among others.

Rust and Corrosion Inhibitors

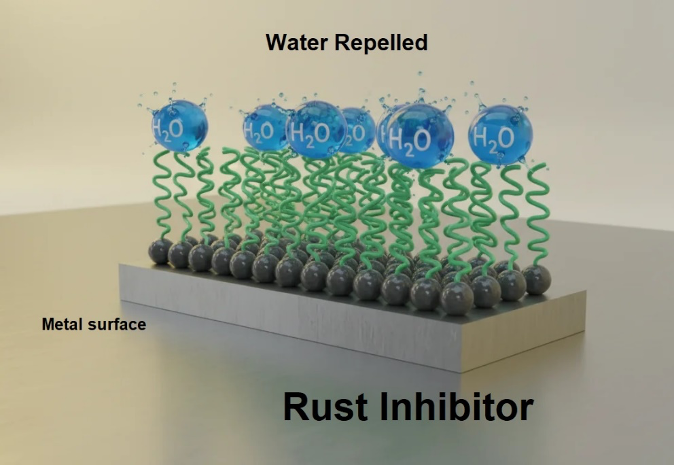

Rust forms when iron-containing materials react with water and oxygen, while corrosion more broadly results from chemical or electrochemical interactions between a material and its environment. Rust and corrosion inhibitors, which are widely used in most lubricating oils and greases, help prevent internal metal degradation by neutralizing acids and forming a protective barrier that repels moisture from metal surfaces (Figure 2). Some inhibitors are formulated to protect specific metals; therefore, a lubricant may contain several corrosion inhibitors to ensure comprehensive protection.

Figure 2

Anti-wear (AW) Agents

Mechanical wear manifests in several forms within lubricating systems, including abrasive wear, adhesive wear, spalling, and pitting. The primary role of Lubricant additives as anti-wear (AW) agents is to protect loaded metal surfaces from wear, especially under mixed or boundary lubrication regimes. When metal surfaces come into contact, these agents undergo chemical reactions with the metal. The frictional heat generated at the contact points activates them, enabling the formation of a thin protective film that minimizes wear and surface damage. However, over time, these additives are gradually consumed and degraded, increasing the risk of surface wear and localized damage.

In addition to reducing wear, AW agents contribute to oxidation control by protecting the base oil and preventing acid‑induced corrosion of metal components. Among the most widely used anti-wear additives are phosphorus-based compounds, particularly zinc dialkyldithiophosphate (ZDDP). Other wear-prevention agents include molybdenum-based compounds such as dialkyl dithiophosphates and dithiocarbamates, as well as several organic compounds and metallic detergents.

At elevated temperatures, AW additives decompose at the metal‑to‑metal interface and react with the surfaces to form low‑friction, protective layers. Over time, these additives are gradually consumed and degraded, increasing the risk of surface wear and localized damage.

Extreme Pressure Additives

Extreme pressure (EP) additives are more chemically aggressive than anti‑wear (AW) additives and become effective only under high‑temperature or heavy‑load conditions. Under such severe operating regimes, these additives chemically react with sliding or loaded metal surfaces to form thin, insoluble protective films that prevent seizure and excessive wear.

It is important to note that even in the presence of EP additives, some wear may still occur during the initial break‑in period, before the protective layers have fully developed on the metal surfaces. EP additives commonly contain sulfur‑ and phosphorus‑based compounds, and sometimes boron derivatives, which provide the necessary reactivity under extreme conditions.

Because different metals exhibit varying chemical reactivity, EP additives must be carefully formulated for compatibility with the specific materials in the system. For example, additives designed for steel‑on‑steel contacts may not be suitable for bronze components, since bronze is less reactive and does not readily form the same type of protective EP films.

Viscosity Index Improver

The viscosity index (VI) is a measure of how a lubricant’s viscosity changes with temperature. A higher VI indicates that the oil maintains a more stable viscosity as the temperature rises, ensuring consistent lubrication across a broad temperature range. Viscosity index improvers are usually long‑chain, high‑molecular‑weight polymers that adjust their molecular configuration with changing temperature.

At low temperatures, these polymer chains coil tightly, minimizing their effect on viscosity and allowing the oil to remain fluid for easy circulation and improved cold‑start performance. In contrast, at high temperatures, the chains uncoil and expand, helping to increase the effective viscosity and maintain film strength between moving parts. This adaptive behavior improves wear protection, low‑temperature flow, and fuel efficiency.

VI improvers are particularly important in multi‑grade engine oils, as well as in hydraulic and gear lubricants that must perform reliably under both cold‑start and high‑load conditions. The most common VI improvers are olefin copolymers (OCPs), although other types are also used. One key limitation of VI improvers is mechanical shear, in which internal engine or gearbox forces can break the large polymer chains into smaller segments, reducing their thickening capability. Hence, selecting high‑quality, shear‑stable VI improvers is essential to ensure long‑term viscosity control and lubricant performance.

For a deeper understanding of how the base oils themselves influence viscosity behavior, oxidation stability, and overall lubricant performance, you can explore our related technical resource: Industrial Oils; Characteristics, Classification & Application.

Pour Point Depressants

The pour point of a lubricant is the lowest temperature at which it remains fluid enough to flow. Pour point depressants (PPDs) are additives that enhance the low‑temperature fluidity of oils by modifying the formation and structure of wax crystals present in the base oil. These additives reduce both the size of the wax crystals and their tendency to interlock, allowing the lubricant to flow even at sub‑zero temperatures.

Although PPDs cannot completely prevent the formation of wax crystals, they lower the temperature at which these rigid structures begin to form. Depending on the formulation, PPDs can achieve pour point reductions of up to 28 °C (50 °F), with typical improvements ranging between 11 °C and 17 °C (20 °F – 30 °F). However, solubility limitations in certain base oils may restrict their overall effectiveness.

Pour point depressants are particularly important in automotive, hydraulic, and gear lubricants that must retain adequate flow characteristics under cold‑start or extreme low‑temperature conditions.

Detergents

Detergents perform two key functions in engine oils: they keep hot metal surfaces clean by preventing deposit formation and neutralize acidic by‑products generated during fuel combustion and oil oxidation. These additives are alkaline (basic) compounds that maintain the oil’s reserve alkalinity, quantified as the Base Number (BN).

Modern detergent systems primarily contain calcium and magnesium sulfonates, phenates, or salicylates, which provide both cleaning and neutralizing capabilities. Although barium‑based detergents were once widely used, environmental and health concerns have largely eliminated them from current formulations.

A drawback of metallic detergents is that they produce ash residues when the oil is burned, potentially leading to deposit buildup in high‑temperature applications. Consequently, many original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) now specify low‑ash or ashless lubricant formulations for engines and machinery operating under severe thermal conditions.

Detergents are typically used in combination with dispersant additives, which help suspend and remove contaminants, together maintaining both engine cleanliness and acid‑base balance over extended service intervals.

Dispersants

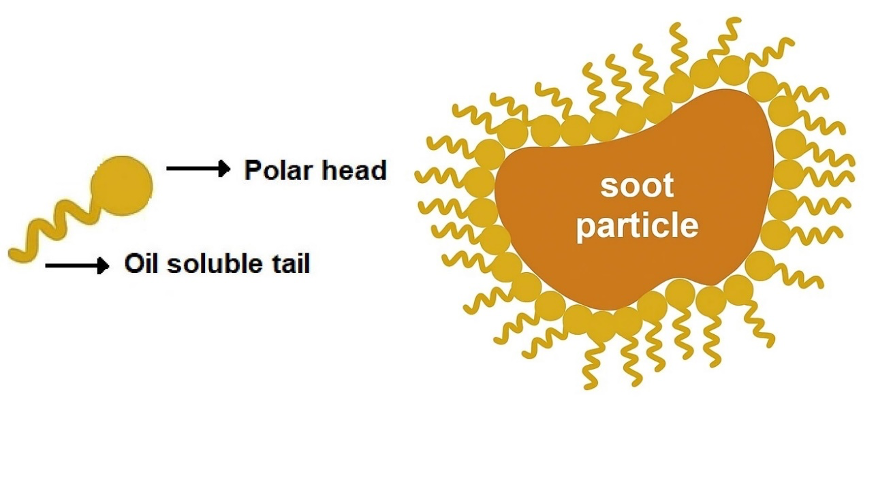

Dispersant additives are mainly used in engine oils, where they work together with detergents to keep engines clean and free from harmful deposits. Their primary function is to stabilize soot and other insoluble contaminants generated during combustion by maintaining them in a finely dispersed or suspended state within the oil, typically smaller than one micron in size. By preventing particle agglomeration and settling, dispersants minimize wear and enable the safe removal of these impurities during an oil change (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Unlike metallic detergents, dispersants are organic and ashless, commonly derived from polyisobutylene succinimides (PIB‑SI) or similar polymeric compounds. Because they contain no metal, they are difficult to detect through conventional oil analysis, despite playing a critical role in cleanliness retention.

The combined action of detergents and dispersants allows engine oils to neutralize acidic by‑products and maintain fine contaminant dispersion over extended service intervals. However, as these additives gradually become saturated through acid neutralization and contaminant load, their effectiveness declines, signaling the need for an oil change to restore performance.

Emulsifiers/Demulsifiers

Emulsifiers are added to oil–water‑based metalworking fluids and fire‑resistant hydraulic fluids to help form and stabilize uniform oil–water emulsions. These additives act as molecular bridges at the oil–water interface, reducing interfacial tension and enabling the two otherwise immiscible phases to remain blended. Without emulsifiers, oil and water would separate naturally because of their differences in surface energy and specific gravity. The balance between hydrophilic and lipophilic groups within an emulsifier, often expressed by its HLB (Hydrophilic–Lipophilic Balance) value, determines the stability and type of emulsion formed (oil‑in‑water or water‑in‑oil).

Demulsifier additives, by contrast, are used to break or prevent stable emulsions. They achieve this by altering the interfacial tension of the oil phase, which allows small water droplets to coalesce and separate more readily from the lubricant. Common demulsifiers include polyacrylates, polyamines, or silicone‑based surfactants designed to promote water release.

Effective demulsification is particularly important for lubricants that operate in humid or steam‑rich environments, such as turbines, compressors, and paper‑machine oils. In these systems, rapid separation of water allows it to settle and be drained easily from the reservoir, maintaining lubricant integrity and preventing corrosion.

Summary

Lubricant additives are chemical compounds blended with base oils to improve their performance, durability, and protective capabilities under diverse operating conditions. While the base oil provides the essential lubricating film, it alone cannot ensure adequate protection against oxidation, wear, corrosion, or thermal stress. Lubricant Additives, whether organic or inorganic, modify the chemical and physical properties of lubricants to enhance efficiency and extend service life. These compounds include various types and categories, each with a specific function; from controlling viscosity and preventing deposit formation to maintaining system cleanliness and smooth operation at high temperatures and loads. The correct selection and formulation of lubricant additives, based on base oil compatibility and system requirements, are vital for ensuring reliable performance, energy efficiency, and reduced maintenance across industrial and automotive lubrication systems.

Frequently Asked Questions

Lubricant additives improve the performance and durability of base oils by reducing wear, oxidation, corrosion, and friction under various operating conditions.

Additives usually make up between 0.1% and 30% of the total lubricant volume, depending on the type of oil and operating environment.

Without additives, the oil would oxidize quickly, lose viscosity stability, cause metal wear, and fail to protect mechanical parts effectively.

AW additives protect metal surfaces under moderate loads, while EP additives are designed for high‑load, high‑temperature conditions where more reactive protection is required.

No. Additives must be compatible with both the base oil and other additives in the formulation to ensure stability and prevent chemical conflicts.

Antioxidants act as sacrificial agents that neutralize free radicals; as they protect the base oil, they are gradually used up and lose effectiveness.

Detergents neutralize acids and keep surfaces clean, while dispersants keep contaminants suspended so they can be removed during oil changes.

It helps the oil maintain an optimal thickness across a wide temperature range, ensuring reliable lubrication during both cold starts and high‑temperature operation.

They modify wax crystal formation in the oil, allowing it to flow smoothly at low temperatures and preventing solidification.

Regular oil analysis and condition monitoring are recommended to detect additive depletion and determine proper oil change intervals.

Home

Home Products

Products About Us

About Us Contact Us

Contact Us

no comment