Lubrication:EverythingYou Need to Know About the Basics

1. Lubrication

Lubrication is the process of introducing various substances between sliding surfaces to decrease friction and prevent or control wear. The most common industrial lubricants primarily consist of oils, known as base oils, which can be mineral, synthetic, or vegetable-based.

Choosing the right oil depends on the specific applications in which it will be used. While vegetable oils may be selected when environmental concerns are a priority, they are rarely used for industrial purposes due to their lower oxidative stability and limited flow properties in cold temperatures. In contrast, mineral and synthetic base oils are more commonly utilized in industrial applications, with synthetic oils proving beneficial in extreme conditions.

Mineral And Synthetic

Mineral oils are derived from crude oil, and their quality largely depends on the refining process. They consist of four different types of molecules: Straight paraffin that has a long, straight-chain structure. Branched paraffin has a similar structure to straight paraffin but includes side branches. Naphthene features a saturated ring structure and is typically used in moderate-temperature applications. Aromatic that have a non-saturated ring structure, are mainly utilized in the production of seal compounds and adhesives.

Synthetic oils make up a smaller portion of industrial lubrication oils mainly because of their higher cost. These oils are composed of highly modified man-made molecules and are available in several types, each with different properties. Synthetic oils are often chosen for specific applications due to their distinct advantages, including improved oxidation stability, enhanced thermal resistance, and a higher viscosity index.

To enhance specific characteristics of base oils, various additives are incorporated. For example, in situations where temperatures fluctuate significantly, a viscosity index (VI) improver might be included. VI improvers are composed of large organic molecules that remain coiled at lower temperatures but expand as the temperature increases. This structural change influences the oil’s viscosity, improving its flow in cold conditions and sustaining its performance at high temperatures. A disadvantage of using additives is their potential for depletion, which necessitates oil replacement to ensure properties remain adequate.

2. The objectives of Lubrication

While reducing friction is the primary goal of lubrication, there are several additional benefits associated with this process. Lubricants can minimize wear by creating a film that effectively separates surfaces, preventing them from rubbing against each other. They also help prevent corrosion by forming protective layers that shield surfaces from corrosive substances, such as water.

Lubrication is crucial for controlling contamination in systems. The lubricant acts as a medium that transports contaminants to areas where they can be easily removed. Additionally, lubricants are essential for managing heat buildup in machines; they absorb heat from surfaces and transfer it to cooler areas where it can be dissipated. This is particularly relevant for oils that are circulated within the systems.

3. Types of Lubrication

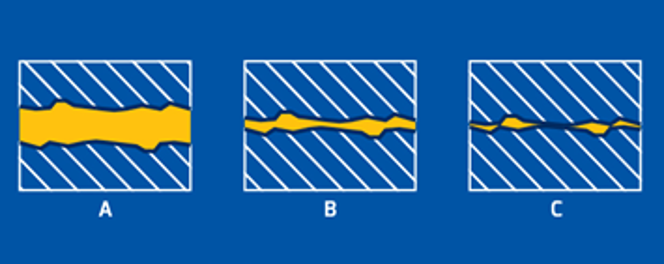

Lubrication is typically categorized into three types: full film, boundary, and mixed. Although each type functions differently, they all depend on the lubricant and its additives to provide protection against wear.

3-1. Full-film

Full-film lubrication is a standard mode of lubrication in which a lubricant creates a thin fluid film layer that separates the surfaces of the bearing. This fluid layer becomes pressurized, allowing it to support the load transmitted across the bearing surfaces. By preventing direct contact between these surfaces, full-film lubrication effectively minimizes friction and wear.

Full-film lubrication can be categorized into two types: hydrodynamic and elastohydrodynamic. Hydrodynamic lubrication occurs when two surfaces slide against each other while being completely separated by a film layer of fluid. Even on highly polished and smooth surfaces, there are microscopic irregularities that form peaks and valleys, known as asperities. For full-film lubrication to be effective, the thickness of the lubricating film must exceed the height of the asperities. The film thickness is typically on the order of a micron or less. This type of lubrication offers the highest level of protection for surfaces and is therefore the most desirable.

Elastohydrodynamic lubrication, on the other hand, occurs when the surfaces are in rolling motion relative to one another. The lubricating film in elastohydrodynamic conditions is significantly thinner than that found in hydrodynamic lubrication, and the pressure on the film is higher. It is termed “elastohydrodynamic” because the film elastically deforms the rolling surface to provide lubrication. This type of lubrication is common in automotive applications, such as the bearings that support the crankshaft of a piston engine and the interface between the cam and follower

3-2. Boundary .

In boundary lubrication, the rolling and sliding bodies are separated only by a few layers of molecules and the film varies in thickness from 1 to a few tens of nanometers. Boundary lubrication occurs when two surfaces come into contact, meaning they are not completely separated. This leads to direct interaction between their microscopic roughness, known as asperities. In these contact points, lubricant molecules form a thin adsorbed film, or a chemical reaction may take place, which provides some protection against wear and friction. However, this thin film may not entirely prevent metal-to-metal contact. Boundary lubrication is common in situations that involve frequent starts and stops, as well as under conditions of shock loading.

Typical applications of boundary lubrication can be found in low-cost, low-speed conditions such as door hinge contact, whereas in other situations, boundary lubrication provides the remedy if the normal lubrication (hydrodynamic or elastohydrodynamic) breaks down

3-3. Mixed

Mixed lubrication, also called partial lubrication, is a combination of both boundary and full film lubrication. Both elastohydrodynamic lubrication and metal-to-metal contact occur in mixed lubrication. While a lubricating layer separates most of the surfaces, some asperities, still come into direct contact with each other. The load is supported partly by the fluid film and partly by the surface asperities.

Gaining a clear understanding of mixed lubrication can provide insight into the broader concept of lubrication itself. Lubrication is a process used to separate surfaces or protect them, aiming to minimize friction, heat generation, surface wear, and energy consumption. This can be achieved through the use of various substances, including oils, greases, gases, or even other types of fluids. The complexity of mixed lubrication highlights the important role it plays in maintaining the efficiency and longevity of mechanical systems. Understanding mixed lubrication is particularly important to a system engineer for the following reasons. First, it is the lubrication regime in which an accurate prediction of the friction is the most difficult, due to the interaction between the complex surface topography and the fluid pressure (or the oil film thickness). Compared to mixed lubrication, hydrodynamic and elastohydrodynamic lubrication regimes are relatively simpler. The calculation of mixed lubrication is also more complicated than that of the boundary lubrication regime. Secondly, mixed lubrication is a bridge between the hydrodynamic (or the elastohydrodynamic) and the boundary

lubrication regimes for a system design engineer to fully understand all the links between them. Thirdly, engine lubricating oil film breakdown and wear (a durability concern) start from mixed lubrication.

Many engine components operate in mixed lubrication, for example, the piston rings and the cams. The engine bearings may also operate in mixed lubrication under severe instantaneous loading.

Film condition in various lubrication modes is depicted in the figure below. In boundary lubrication (c), the asperities touch, whereas they are fully separated in full film lubrication (a).

Home

Home Products

Products About Us

About Us Contact Us

Contact Us

no comment